Josette Pringle lived a life full of interest and exploration that took her to some less-visited corners of the world. She was intelligent and well-read, and took a keen interest in many subjects, especially archaeology, religion, spirituality, history, and culture. She was trained as a librarian and had a degree in archaeology and a BA in anthropology and theology. Josette was born with a congenital heart defect, and spent many years of her childhood in hospital. She died much too young at the age of 44, in Auckland. She was my paternal aunt, the older sister of my father Derek Pringle.

Early Life

Josette Lena Alys was born on 3rd April 1930 to William Pilliet Pringle and Norah Burt, who lived for all their married lives at Messines Road in Karori, Wellington. The family house was firstly at No.86 Messines Road and then the family moved on to a rear section, No.88.

Her first name Josette is French and may have been suggested by Josette’s father’s mother, Lena Pringle, who had been to France (her father was French-born) and apparently liked that name(1).

Her second name Lena was taken from her paternal grandmother, whose name was Hannah Caroline Pilliet but was usually known as Lena.

Alys is a variation of Alice, the name of her maternal grandmother.

From about 1936 Josette attended a private school at 70 Friend Street, Karori, officially known as Welby Kindergarten and Preparatory School, where the emphasis was on imaginative play and dancing rather than the “3Rs”. The children wore a brown and yellow uniform. The school was small and intimate, with never more than 30 pupils. Clearly Josette’s imagination and abundant curiosity were stimulated by the active style of teaching (2). The pupils were encouraged to climb the huge macrocarpa trees on the property and read books in the branches, or to do gymnastics.

In 1937 Josette took the part of a plantation worker in an entertainment called “Old King Cotton”, one of three “American playlets” written by Miss Robina Green, principal of the school. The playlets were performed by the children for their parents and possibly the public. Miss Green was fond of productions: on 28th October 1938 the school performed a Japanese play, “Fuji-yama” in the St Mary’s parish hall in Karori, charging 1s for adults and 6d for children (3).

1950s Wellington

1950s Wellington was not a place of boring provinciality as it is sometimes characterised. It may have been moderately prudish, but “Wellington was unselfconsciously Bohemian”, Jocelyn Chisholm has written in her memoir of the New Zealand painter Bruce Henry, the “stage was lively with theatre and music and there was no shortage of encouragement to animate artists, writers and performers.” (6) Rapid changes were occurring in the look of cities with the arrival of modernism and increasing urbanisation and the development of motorways and suburban shopping centres. The Wellington Architectural Centre gave stimulus to a new wave of modernist architects. “These were formative years for arts journals and non-institutional galleries, and the fledging ventures had impact and influence”, note Julia Gatley and Paul Walker in their book on modernism in 1950s and 60s Wellington, Vertical Living (7).

Josette attached herself to these emerging trends. She met Kenneth Bryan who had been living at the home of the artist Bruce Henry at 444 Muritai Drive, Eastbourne in the early 1950s. On the 6th March 1954, aged 23, Josette married Ken at St Mary’s Church in Karori, Wellington.

In 1957 Ken and Josette were living at 28 Clifton Terrace in Wellington.

In October 1957 Josette volunteered as a minder at the Architectural Centre Gallery at 288 Lambton Quay, Wellington, during the exhibition of paintings by Bruce Henry. She most probably met Henry at his house in Eastbourne where her husband Ken had been living prior to his marriage. Later she writes that did know Henry, and that not only was he a painter whom she clearly appreciated, but he was also a “magnificent cook”.

The gallery, opened in 1953, was the focus of much of the cultural life of 1950s Wellington. It was attached to the Wellington Architectural Centre. It was committed to showcasing international, and modernist, art, and saw itself as a civic non-commercial institution, akin in values to a national art gallery. It had come to be recognised as “New Zealand’s leading showcase of art for sale”, wrote Betty McKinnon in the Dominion newspaper in May 1956. “How about going to the Architectural Centre Gallery after lunch? That is an appointment that Wellington clerks, typists and businessmen often arrange…because the gallery is situated right in the middle of the city. Unpaid staff, a steep climb up stairs to the second floor overlooking the traffic of Lambton Quay…with mostly free exhibitions. The person at the door was as likely as not to be a housewife sitting in a small chair mending children’s socks” wrote Ms McKinnon.

Josette was, however, not a sock-mending housewife. She was keenly interested in art. She kept a short diary of her time minding the Henry exhibition, a copy of which is at the Te Papa Museum Library in Wellington. Josette’s understanding eye and mind are much in evidence in the diary – she records her responses to the paintings as well as those of some of the visitors to the gallery.

Josette’s feelings about what she perceived as the limitedness and anxieties of New Zealanders in the 1950s are revealed in some of the diary comments. She writes that she opened a Remarks Book but no comments were entered for two days. “It was not that people had nothing to say about the paintings…but probably that they suffered from the New Zealander’s usual temerity in expressing an opinion about anything “arty”. (4)

The ill-informed remarks of many visitors left Josette exasperated, and she vents her frustration into the diary: one woman remarking she did not like the frames; a man complained that the pictures were too complicated – “well why not complicated, you b… ape!” she exclaimed onto the page; another woman said ” ‘they’d all be better unframed’. People really are extraordinary.”

Damian Skinner, in a paper published in Art New Zealand, has analysed Josette’s diary in depth and posits that it has a special interest as it not common to find sources which attempt an interpretation of the audiences visiting modernist galleries at this time. He noted that Josette believed that many viewers “manifest a desire to locate the artworks in a context of artistic practice, and take part in a discourse of sources and influence that includes paying attention to reviews and critical responses”. Josette in the diary notes that people have a “passion for likening. Maybe they are in part right. All art is derivative”. Her view was that we defer to authoritative opinion rather than simply look, and respond on an intuitive and personal level. But Skinner takes another view: Josette’s diary “perhaps allow[s] argument that art viewers in the 1950s were literate in art history and in viewing exhibitions, and quite willing to engage with international art…” and that they drew on their knowledge of art history “to negotiate with the new works on display”.(8)

Dr W.B Sutch was the voluntary Chairman of the Gallery Committee from 1956 to 1958, and although Josette was one among many volunteer minders, it is possible that their paths crossed at this time, perhaps at Gallery functions. It is not known if Josette acted as volunteer minder at other Gallery exhibitions although it appears unlikely.

Josette and Ken had moved that year to 9 Benzie Avenue in Upper Hutt. The marriage was a not success, however. Ken left Josette without explanation and Josette filed for divorce in October 1968. This was granted by the Auckland High Court on 29 April 1969.

In June 1966 Josette visited Fiji. She was on a three-week study tour as part of her studies at Auckland University in anthropology and comparative religion. Part of her duties included helping at the Central Archives in Suva to catalogue official Fiji government publications (10).

On her return to New Zealand she noticed an article on the practice of firewalking in Fiji and other Pacific territories in the journal the Pacific Islands Monthly of May that year, by Philip Langdon. Langdon considered various explanations for the ability of islanders to walk barefoot across apparently searingly hot rocks and reported on a study done which showed that the types of rocks used were poor conductors of heat, and concluded that it was therefore possible to walk across them without suffering severe injury.

Josette, in a letter published in the July edition of the magazine, noted that various non-Western cultures do, or have, practiced forms of ordeal by fire which the practitioners can endure unscathed if they have sufficient belief, and that “certain higher psychic forces” can work through a person to enable them to perform such feats. Josette believed that we can have conscious control of metaphysical forces, which, she admitted, are “not very measurable”, but are, she said, “real and operative, for all that”. (9) She claimed that some can form a “force field of certain currents” and that this is known to Indian yogis among others, but she was not, at least then, able to say what these force fields or currents actually consisted of. The Fijian medical practitioner she spoke to about the firewalking practice stated that a form of spiritual purity was required to perform such feats; that by combining both mental and spiritual energy, people were able to control psychic powers in their own body.

It is likely that Josette studied anthropology in pursuit of her spiritual quest; to deepen her belief that there is more to existence than can be explained by science or medicine, and that the existence of such practices of endurance throughout the world offered evidence of the truth of these “higher forces”. Josette’s inquiries thus rested somewhere between the Western, deductive view of the universe and a quasi-Eastern mysticism that relied on spiritual explanations: or even, as she must have believed, that explanations are beside the point. Simply acknowledging the inherent truth of these practices was sufficient: and that by believing strongly enough, one could also participate in these practices and benefit from them. By describing herself, rightly, as a student of anthropology and theology, Josette sought to place her letter and views in an academic sphere, but was not able to provide explanations other than that “certain currents” and “higher forces” were at work.

She was engaged in a quest, however, and this was primarily a spiritual one, and not one that aimed to reduce the object of her studies or to deconstruct it any way: simply to study, and to learn. I think this was a guiding principle through her life: that beliefs and wisdom had no less legitimacy or agency if they were “unproveable” or could not withstand scrutiny from academic inquiry. Firewalking was not bogus simply because those from the West who came to examine and explain practices from other cultures ended up not being able to explain it.

In 1969 Josette graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from The University of Auckland; the conferment ceremony was held on the 9th May.

Josette went to South Korea in April 1970 to work as the Centre Librarian at Asia and Pacific Council (ASPAC) in Seoul. ASPAC is now disbanded.

Above is a photograph Josette took in October 1970, a typical Seoul street view on her way to work every day, she noted.

Above is a photograph Josette took in October 1970, a typical Seoul street view on her way to work every day, she noted.

Seoul was at that time experiencing severe smog pollution problems, and Josette offered a poem to the English-language newspaper in Seoul, The Korea Times. She wrote that “…I find myself moved, in Korean fashion, to express in poetry the beauty of the city after rain(5):

Blessed rainfall Settles city smog, Smacks on pavements, Gurgles in the pipes. Wet rock walls glow With apricot light; A roof reflects Lamplight wetly. Buildings blink With emerald eyes. As the mountains clear, My spirits rise. Below is a Seoul street scene Josette also photographed, showing the poverty and simplicity of lives at that time.

Josette joined the Korea branch of the Royal Asiatic Society which held regular meetings and talks in Seoul, thereby deepening her understanding of Korean life and culture (11).

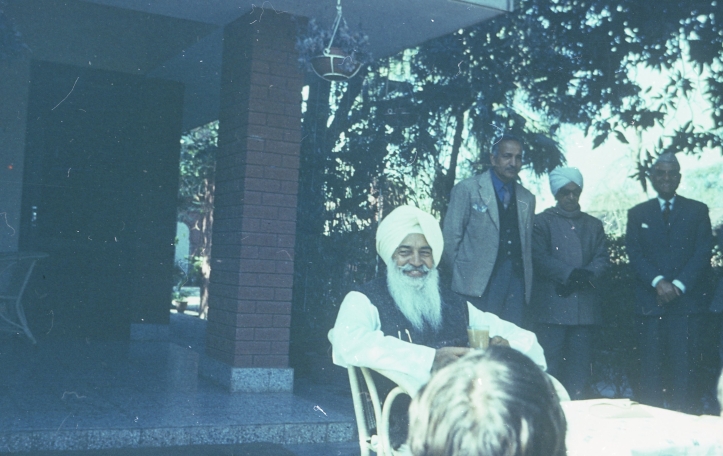

Picture below is of Josette at The Dera, or Ashram, which she visited in India.

Return to New Zealand

On returning to New Zealand Josette applied for and was successful in obtaining a position as Librarian at the Forest Research Institute in Rotorua. The Institute did not have a formal library until 1972, when in April they appointed a Librarian. By 1973 Josette was making a significant impression on the library, increasing the stock to the tune of 1,410 new books and 1,443 serials monographs. The total stock increased to 51,200 items.

The 1974 annual report of the Institute noted that the library did not have a librarian for the latter part of the year due to Josette’s resignation.

Sources:

(1) Email communication from my father Derek Pringle, 14 May 2014.

(2) Karori and its people, Karori Historical Society, 2012, ed Judith Burch and Jan Heynes; “Stockade”, journal of the Karori Historical Society, Sep 1986 Vol 14 no.9.

(3) Evening Post 22 October 1938, page 4.

(4) “Paintings by Bruce Henry, 29 October to 8 November 1957”, A Diary by Josette Bryan, held Te Papa Museum Library

(5) Korea Times (Seoul). 16 May 1970 p.2

(6) Artist and bon vivant: a memoir of Bruce Henry, Norma Ashworth and Jocelyn Chisholm, 2001. p.17

(7) Vertical Living: The Architectural Centre and the Remaking of Wellington, Julia Gatley and Paul Walker, Auckland, 2014, p.53

(8) Modernism and its audience: paintings by Bruce Henry, Architectural Centre Gallery, 29 Oct to 8 Nov 1957. Art New Zealand, Summer 2003.

(9), Letter to “Editor’s mailbag”, in Pacific Islands Monthly, July 1966, pp50-51.

(10) Fiji Times, 10 May 1966, p.2

(11) List of members in Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch, Vol XLVI, 1971 (accessed at http://anthony.sogang.ac.kr/transactions/VOL46/vol046.docx on 30 April 2019).

(12) Annual Reports of the Forest Research Institute. Rotorua, 1972-1974 (NZ Government Printer)

Some very interesting and informative details on my cousin, Josette.